Notice: Undefined index: description in /home/erikphillip/public_html/conflictresearchgroupintl.com/wp-content/plugins/draw-attention-pro/public/includes/pro/pro.php on line 250

The Legal Use of Force

Legalities. Self-defense is a legal concept, not a physical system. As such, if you claim to teach or study self-defense, you are teaching and or studying law. Don’t nut up on it. Generally, people raised in a culture have instincts in line with that culture. Law is just a codification of cultural values.

For students and teachers both:

Have you read the self-defense statutes for your state and neighboring states?

Do you understand them?

Did anything in those statutes trigger a glitch?

Can you see the commonalities and the differences between the laws in different states?

Do you know the process of being investigated, interrogated (know the difference between an interview and an interrogation) and arrested?

Do you know how both the criminal and civil court systems work?

Are you skilled at arguing an event so that you can tell the important parts of the event as a narrative?

Do you have a plan on who to talk to, when and how much to say in the aftermath of a catastrophic event?

Do you have an attorney who is good at SD law and affirmative defenses?

And, additional for instructors:

Has any course you teach on this subject been vetted by a practicing attorney?

Have you examined your physical curriculum with an eye to its legality? Are you teaching students to go to prison?

Prevention

We all play lip-service to the concept that it is better to avoid fights, but for most it never goes beyond lip service. It’s not enough to say that you will run away, you must practice. It’s not enough to tell your students to apologize or to set boundaries, they must practice. More importantly, they must be rewarded by the instructor for soft skills working.

We all know that a soft win is a better win. If you avoid the situation entirely, no one gets hurt, no one gets traumatized-- hell, you don’t even know for sure if something bad was going to happen. If you get out of there, again, no injury on any side, no paperwork. Same if you talk your way out. A perfect win has no injuries and no regrets. Avoidance, escape and de-escalation give you a shot at a perfect win, and we all know it. But they must be practiced just like any other skill.

Avoidance; Escape and Evasion; De-Escalation

For students:

Do you know the places where bad things are likely to happen?

Do you refuse to lower your guard (e.g. drink alcohol) in those places?

Do you know how to tell when you don’t know the social rules in a given place?

Do you have a strategy for avoiding conflict in an unfamiliar place? Have you tested it?

Can you apologize sincerely if it is the right thing to do? Will your arrogance convince you it isn’t the right thing to do?

Do you habitually notice exits and possible alternative exits (like breaking windows) in your environment?

Do you know the difference between cover and concealment?

Do you have plans for bad things happening in your home that your whole family knows?

Do those plans include a rally point where everyone is to meet? (Super basic rule: You never run away from danger, you run towards safety.)

Can you distinguish between ego and real loss?

Can you sacrifice ego/pride to avoid using force?

Do you recognize that the de-escalation for predatory threats is different than for threats acting from ego motivation?

Do you have the acting skill, and the humility, to change your voice, demeanor and attitude and to do so under stress?

Can you yell for help?

Can you break your social conditioning enough to make a scene?

Can you recognize the manipulatable social dynamic in a situation, e.g. get other people to take your side or appeal to a higher status gang member to intervene?

For Instructors:

Have you ensured that your students have actively practiced avoidance, escape and de-escalation?

More importantly, have they been consistently rewarded for NOT fighting? If you say the words “run” but, when a student actually runs, you tell the student they did it wrong, what you are training is not in line with what you are conditioning.

Violence Dynamics

You must study problems in order to find solutions. If SD techniques are the answers, Violence Dynamics is the study of the problem. This is a sticky section of the map, because I have designed models that I am very happy and successful with, but they are models, not truths. So it will take some work to be sure that I’m making a checklist for you, not a checklist of my path.

For students:

Do you understand the difference between someone who has a personal issue with you, someone who wants your money and someone who wants to have fun with your pain?

Can you distinguish the behaviors between those three?

Do you understand the qualitative difference between the three types of threats?

Do you recognize that a threat acting from an altered state of consciousness is yet another qualitatively different problem? And do you know the nature of that problem?

Can you read terrain to know ambush zones, escape routes, where movement is limited or easy and where visibility is limited or easy?

Can you see and explain the differences in normal and abnormal distancing and posture?

Recognize the body language of a person concealing a weapon?

Do you recognize the signs of adrenaline?

Can you recognize the signs of someone trying to control his or her adrenaline level?

Do you recognize a criminal interview?

Can you distinguish your social, psychological and verbal options as they exist early in an encounter?

Do you know your own threat profile?

Do you understand what a criminal needs in order to be successful in a crime and, therefore, what you must deny a criminal?

For Instructors:

Do you have a model that makes it easy for your students to understand the differences between criminals?

Is that model useful-- in other words, can it accurately predict danger?

Is the model designed in such a way as to get past student’s psychological resistance to the concept of evil?

Have you vetted that you teach defenses to attacks that actually happen, not ones that are easy?

Is any scenario training you do based on real crimes? Or is it back-engineered from the results that you want?

The "Freeze"

People freeze. When completely surprised, even well-trained and experienced fighters have a very small freeze as they switch gears. The freeze is even greater when adjusting to an unfamiliar situation. The best fighter in the world will have to adjust if attacked by a leopard.

Freezing is also the hardest to train for, because the hindbrain recognizes that training is artificial. Also because it is very difficult to do something completely unexpected in a class format. Therefore, if you have checked off most of these, it will have come from life experience. And, nature of the beast, I can only put on this list the things that stem from my life experience. There are likely levels I can’t even imagine.

For students:

Have you been frozen by surprise and broken the freeze?

Can you recognize a freeze from the inside?

Do you understand that freezing is often the best option?

Have you gained enough experience at one type of situation that the freeze is minimal, just switching gears?

After achieving that level, have you experienced a freeze from a different cause and been back at zero?

Have you tracked the times you have frozen and broken the freeze?

Do you know the pattern to break a freeze?

Can you remember how to break a freeze while in the middle of it?

For instructors, all of the above plus:

Do you understand that freezing happens at a deeper level of the brain than can be accessed by training? That responses must be conditioned, and the stimulus necessary to experience the freeze may be impossible to reproduce? More importantly, are you in denial about the limitations of your training methods?

Do you understand that achieving and defeating the freeze under one set of conditions may have no correlation with success if the conditions change?

Have you made your students aware of these limitations?

Counter-Assault

Good understanding of violence dynamics coupled with avoidance/E&E/de-escalation skills will prevent almost everything. But not everything. In a perfect world, things should only go physical if you didn’t see it coming. In reality, things can go physical if you don’t see it coming, if you misjudge the situation (and experienced criminals are masters at getting victims to misjudge the situation), if you are in denial about what you do see, if you make a mistake, or if you are too arrogant to walk away. There may be some other problems, but that’s the short list.

Which means that when it goes physical, it will probably be a surprise. Which means you have to have something to get past an ambush or sucker punch in one piece.

For the record, I teach (condition) separate responses for attacks from behind.

Counter-Assault

For students:

Do you have a technique for getting past a sucker punch or ambush?

Will it work without modification regardless of whether the attack is right or left, high or low?

Is it a “golden move” in that it protects you, injures the threat, puts you in a better position and puts the threat in a worse position in a single action?

Is the technique robust? In other words, does it still work very well if you do it mostly wrong?

Have you trained it to reflex?

For teachers:

Does whatever you teach satisfy the requirements listed above?

Do you understand the difference between training and operant conditioning?

Are you careful to condition, not train, the counter-ambush techniques that you teach?

The Fight

Most martial artists and most self-defense instructors spend most of their time and effort on this physical aspect of the problem. It is by far the least important. Avoidance is always better, as is escape. And in self-defense, the common physical problems are rarely what people train for. How a 200-pound, fit, life-time martial artist might defend himself if challenged in a pub is a paltry problem. The question for self defense is how does a petite, tipsy woman who has little time to train and years of social conditioning to be nice survive when targeted by a larger, stronger, vicious, experienced guy who gets the first move from total surprise.

If you think that is an insurmountable problem, you are thinking like a fighter. That is something you must outgrow if you want to teach self-defense or even successfully defend yourself.

The Fight

I’m not including a checklist in this section. One is available, don’t get me wrong. But there are certain things that are bad ideas to just read. If you read a list, a good list, your brain says “good enough” and stops. For example, there are a few instructors I admire, but I don’t read or watch or participate with their material. I want to develop my own stuff. BUT, if one asks me a question, we’ll both develop answers and share the finished product, and that gives us two good answers to compare, contrast and maybe blend. Getting answers too early in your own process is a pollution that kills creativity. Comparing your completed ideas with someone else’s is crosspollination of the highest order.

So I’m not giving you a checklist. I want you to make your own. Once you have done so, feel free to get a copy of my book, “Chiron Training Journal” and compare our efforts.

What should be on the check list? From the book:

Building Blocks are the basic classes of techniques. They are also the ‘sweet spot’ for codifying useful information. Humans can look at the same things in big, sweeping generalities (impact!) or in tiny detail (middle- knuckle extended horizontal fist.) Too much detail and you have fighters trying to fight from memory, using the wrong part of their brains. Too general, and it is almost impossible to teach and therefore impossible to learn. “Become one with your opponent” is both a complete fighting philosophy and completely useless.

So this section is just a list of your building blocks, broken down the way that makes sense to you. You might have ‘Hand strikes. Knee strikes. Kicks. Elbows. Head butts.’ For five things. Or cover the exact same material with ‘Power generation. Targets. Weapon conformation.”

It’s just a list. If you need more than two pages you are probably, in my opinion, breaking things down too far. But I could be wrong.

Principles are the things that make other things work. When you discover something common to all systems, grappling, striking, throwing or weapons, you have a principle. One example is leverage. Good leverage makes things better. Poor leverage makes things worse. I’ve only identified a handful of really universal principles and some of them are lumps of ideas. You’ll get it when you see my list. After you write yours, please.

Concepts are the ways of thinking. If you are good at anything—driving, writing, fighting, anything—you do not think about that subject the way a beginner thinks. A blackbelt doesn’t look at questions the same as a beginner...and someone who has had a hundred fights doesn’t look at them like a blackbelt.

Changes in thinking are almost invisible. Once you learn to see or think in a new way, you will think that you have always known it. You will notice your changes by listening to beginners.

Make your own checklists on these three levels. Students need to know if they are competent at all the things on the list. Instructors need to know if they can teach them.

The Aftermath

Ideally, this material should be written by a psychologist, a police intelligence officer local to the area, an attorney, a paramedic, an ER doctor, and a physical therapist.

One of the subconscious myths of self-defense is that you can get involved in violence, save your life, and nothing will change. In truth, there is no consequence-free way to use force on another person. At minimum, your first violent encounter will irrevocably change what you think you know about the world. There will be actual or potential legal, psychological, social and medical consequences. It will happen. To ignore this is to set your students up for failure in the second battle.

There are four elements of potential aftermath: retaliation, medical consequences, legal consequences and psychological/social consequences.

What you should know and what you should teach depends very much on your relationship with your students and your particular circumstances. For instance, though it may be difficult to find out or stay current, if you have a student base in a single city, it would behoove you to know the local gangs, the local criminal families (not organized crime) and their attitudes towards “respect” reputation and retaliation. If you do traveling seminars, that level of local knowledge is simply not possible.

Therefore, what follows will be extremely generic. Do not consider it a comprehensive checklist. At best, it will be a starting point.

Overall, though:

Do you have a protocol for what to do immediately after a self-defense incident?

Have you practiced that protocol?

If you are an instructor have you made your students practice?

RETALIATION

For students:

Have you done a personal victim profile?

Of the profile types, is there a specific demographic or group that is more likely to target you?

If so, what can you find out about the group?

Are you mentally prepared to go on high alert for a considerable period of time after a violent encounter? Is your family?

Do you have a plan, including a “go button” for when to disappear? It’s extreme and almost no one has to worry about it, but don’t avoid thinking about it. There are certain groups that I never intend to get on the bad side… but if I did, I’d vanish.

For instructors:

Have you developed sources such that you could find out about a group that might be targeting a student?

Do you have emergency protocols for evacuating your training area? (Not just for violence, you need them for fires and earthquakes as well. Disaster planning is disaster planning.)

As a teacher, in order to be successful, you have to have at least some public presence. Is there a barrier between your public persona and the people you care about? In other words, have you made it at least a little difficult for bad people to find your family?

Have you educated your students on the longitudinal aspect of violence-- before, during and after stuff?

I divide possible medical consequences into short-term, medium, and long term. Obviously, death is a medical issue and is on the table, but “What should you do if you die?” doesn’t make a lot of sense to me.

MEDICAL

For students:

Do you know how to assess yourself for injuries?

What is your level of emergency medical certification? (There’s no reason not to be up to date with at least a first aid certification.)

Have you practiced your first aid skills one handed and blindfolded, on yourself?

Do you know how to call for assistance and what to tell the dispatcher?

Do you have the discipline to follow a physical therapist’s advice no matter how much it hurts?

Are you mentally prepared (can you be?) for the possibility of permanent injury, including brain damage, blindness, paralysis, and shitting into a colostomy bag for the rest of your life?

For teachers:

Having an advanced First Aid and Emergency Care Instructor cert would be ideal.

Do you drill your students on the consequences of the techniques they practice?

Do you discuss the potential physical cost (this ties into ethics as well, everything connects) of individual techniques, but also long-term training?

Do you ever romanticize combat? Or bring up the ‘some things are worth dying for’ while quietly ignoring that very few things are worth being permanently disabled for? Death is easy to romanticize.

PSYCHOLOGICAL AND SOCIAL

I’m well aware that my instincts and beliefs on this subject are outside the mainstream. My stuff works for me, but even professionals mess this up.

For Students:

Are you aware that there is a wide variety of possible emotional reactions to a force incident?

Are you aware that your emotional reactions can change very swiftly?

Are you aware that reactions are normal and most are signs of adjustment, not pathology? In other words, having nightmares, for instance, may indicate that your brain is figuring things out. It may be a sign of healing, not a symptom of a problem.

Are you willing and able to process your experience for growth? That all experiences, no matter how horrible are simply change and experience handling change is the source of strength and resiliency. Do you trust that, eventually, your experiences will make you stronger?

Do you have a circle of experienced friends who can help you process a major life event?

For Instructors:

Do your students trust you enough to share major life events? You cannot force this, demand it or make it happen. This trust must arise because of your nature and must be nourished and never abused.

Are you aware of the signs of self medication or suicidal ideation?

Do you have a list of resources that can help a student?

LEGAL

Ideally, most of what you need to know was covered in the first chapter. But…

For students:

Have you practiced articulating a force incident?

Have you researched and found a good lawyer?

Is the lawyer on retainer or, at minimum, is his or her card in your wallet or number on speed dial?

Do you have a plan for what to say, what not to say, to whom and when?

For Instructors:

Do you regularly have students practice articulating decisions? Do you have them compete in articulation?

Are you competent to judge legal articulation?

Do you understand the rules of evidence in your jurisdiction?

Do you understand and can you explain the differences between potential criminal and civil liability?

Do you understand the process of both the criminal and civil legal systems?

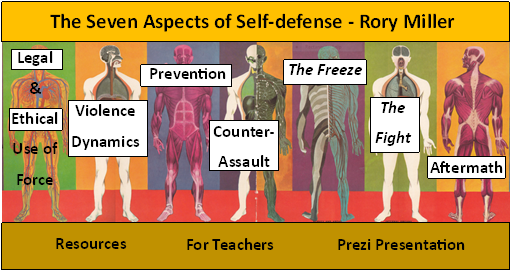

The Seven Aspects of Self-defense

Whether you are a student, practitioner, or instructor, SD is not a simple set of physical skills. At its best, it is an in-depth understanding of a class of problems, combined with social, mental and physical skillsets to neutralize those problems, whether by prevention or direct action.

When we (Kathy and I originally, then Erik) envisioned the maps the idea was to make them a combination of checklist and guide. A list of all the things you need to know and the best order in which to learn them. That way, you could check off your current skills, note and address any holes in your knowledge and plan for the next step in your personal advancement.

I’m going to give it a try. And I hope that each of the CRGI core will do the same in their own areas of expertise. What does a bouncer need to know? An expert witness? A firearms instructor?

Understand that no one knows the answers. We are all limited. And nothing any human can possibly write is a truth. What follows is a model. It is the way I look at things. It may be extremely useful to you, but it is not and never can be the objective truth. In martial arts parlance, it is a way, but not The Way. The only true way is the one you find for yourself. Use my model if it is useful. Make a better model if you can. Always think for yourself-- challenge and question.

That said, in my experience, the smartest, most insightful people are full of doubt. The ones who are actually kind of stupid and unaware tend to have great confidence. So, if you immediately feel comfortable to forge your own way, you’re probably a conceited dick. Forge your own way, definitely, but if you feel comfortable doing so, check yourself. And make damn sure you apply your skepticism and doubt to your own choices just as you would to an enemy’s.

In “Meditations on Violence” and then expanded in “Facing Violence” I asserted there were seven things you must cover in self defense training:

- The ethics and legality of using force

- Violence Dynamics

- Prevention: Avoidance; Escape and Evasion; and De-escalation

- Counter-assault

- Breaking the Freeze

- The Fight Itself

- The Aftermath

These will set the core of the map that follows, with one critical addition at the end.

So, here goes.

- Rory Miller

Ethical Use of Force

Ethics are the internal rules that define your limits. They are idiosyncratic, personal and not necessarily logical. You might be comfortable with killing, but the thought of putting an eye out is disgusting. You might, subconsciously, have entirely different rules about hitting people of your own and a different race.

I will tell you that you need to know your ethics, your internal glitches and freezing points… but you and I need to be honest that you can never truly know them. The nature of limits is that you can’t see them until you hit them. You can be absolutely certain that, if the time came, you could fight for your life… but that certainty appears to have absolutely no correlation with who fights and who freezes. You CAN’T know. But, sometimes, if you keep your awareness up, you can catch hints.

For students have you (or can you):

Hit someone full power?

Been hit full power and got back in the fight?

Been deliberately rude to a stranger? All of self-defense is about breaking social taboos. Setting boundaries and yelling and asserting yourself are all acts of rudeness. Anything more than that-- pushing, hitting all the way up to shooting-- are crimes. If you can’t be rude to a stranger, it is very unlikely you can hit one.

Touch a face and get your face touched? A very common taboo.

Say what you feel?

Set a boundary and refuse to explain?

Slaughtered and butchered an animal?

Injured a human?

Crippled a human?

Killed a human?

For anything you answered ‘yes’ to-- are you okay with what you did?

Understand that the ability to do something and being okay with it are two separate issues. To be able to say that you would kill AND you will lose sleep over killing is not hypocrisy, it is simple maturity. None of this is consequence free and there are many things that seem cool to have done that art extremely unpleasant to do. Past tense improves a lot of things.

For teachers (should know all the student stuff as well):

Can you identify your student’s glitches by the behavior patterns in class?

Have you designed exercises that expose freezing points?

Do you know how to alter glitches by working the underlying issues? By inuring? By finding emotional work-arounds? If all else fails, can you adapt the training around an emotional glitch you can’t fix?

Are you 100% sure about when you are working on your student’s issues and not your own?

Can you tell in the initial interview with a prospective student about what trauma they have experienced and at about what age?

Can you make an emotionally safe place to do physically dangerous things? When, and only when, the student is ready, can you create a physically safe place to do emotionally dangerous things?

Do you grasp the importance of that last bullet point?

Rory Miller

“Force is a form of communication. It is the most emphatic possible way of saying “no”. For years my job was to say no, sometimes very emphatically, to violent people. I have been a Corrections Officer, a Sergeant, a Tactical Team member and a Tactical Team Leader; I have taught corrections and enforcement personnel skills from first aid to physical defense to crisis communication and mental health. I’ve done this from my west coast home to Baghdad. So far, my life has been a blast. I’m a bit scarred up, but generally happy.”

For Teachers

Frankly, there is almost no good material out there for teaching self-defense skills. Self-defense is one of a set of problems with unique characteristics. If ever used, the skills will be used at very high stakes, in a very short time period, with limited information, under emotional/hormonal conditions completely different than the training environment, in a place alien (for most people) to the training environment and, completely without guidance. And, often it is taught by someone who has never experienced these things.

Our usual model of instruction, the kind we all got used to in school, is completely wrong for this. An authority figure telling us what to do mirrors the bad guy-- who may be a man using the authority of a weapon to tell us what to do. Practicing obedience is counter to survival. Doing things by rote, looking for perfection in repetition has no bearing and is not at all helpful in adapting to chaos. Further, if students are constantly corrected, constantly told what they are doing wrong, it sets up an expectation for failure.

What follows are some thoughts for instructors. It may be hard to follow and it may even be hard to research. Without good resources readily available it is extremely unlikely that we will have a common language for this. Looks like I’ll have to write a book.

For Instructors:

Are you familiar with adult learning models?

Do you understand the differences between teaching, training, operant conditioning, and play as teaching methods?

Are you familiar with the uses and pitfalls of those four training methods?

Do you know how to implement them, when to implement them and the potential problems with each type?

Are you alert for any discrepancies between what you are training and what you are conditioning? E.g. In non-contact styles it is very common to train to hit people in the face but to punish people when they make contact. Conditioning contradicting training.

Do you have short-term and long-term lesson plans that cover all seven elements of this map?

Experience in anything high-risk rewires your brain. Can you judge your own experience level and how it has changed the way you think?

Are you aware that there will be students with less, equal or more experience who will think in completely different ways?

Are you aware that people at different levels need and can only apply very different things. E.g. for a student who has never had an encounter, emphasis needs to be put on awareness and emotional strength whereas for an extremely experienced operator it is simply an observation, a decision and applied body mechanics. The refined mechanics that an operator needs will not be accessible or even understood by a rookie. The things important to you at your level may be completely useless to some of your students

Do you have exercises (“play”) that integrate each new skill into an existing framework?

Does the system you teach have a strategy that integrates it, or an image that does so? Do you know what that integrating theme is? Do your students?

Is what you teach internally consistent with the integrating theme?

Do you have exercises that reward the avoidance, escape and de-escalation skills?

Do you have exercises that reward creativity and demand adaptability?

Are you humble enough to reward a student whose solution was more creative than you were prepared for?

Do not ever punish a student for doing well. When a student tags you it is a compliment to your teaching ability. It is exactly what you have been training her to do. If you make an example of that student, you have too much ego for this. You cannot and should not teach self defense.

Are you emotionally prepared for your teaching to fail catastrophically?

Resources

1. Ethics and Legalities

- Facing Violence (Book and DVD)

- Meditations on Violence

- Please Understand Me (not germane to violence, but important for teaching models)

- ConCom

- Drills Manual - Rory Miller

- Jack Hoban and Robert Humphrey’s works

2. Violence Dynamics

- Facing Violence

- Logic of Violence

- Drills Manual

- Marc’s work on the stages of violent crime

- Teja’s Mommy and Me CDs

3. Prevention

- Facing Violence

- ConCom

- Verbal Judo

- The Gentle Art of Verbal Self-Defense

4. Counter-Assault

- Facing Violence

- Tony Blauer

5. The Freeze

- Facing Violence

- The Unthinkable by Amanda Ripley

- Deep Survival

6. The Fight

- Marc’s book on Street E&E

- Facing Violence

7. The Aftermath

- ACLDN

- Facing Violence (Book and DVD)

- In the Name of Self-Defense

- Achilles in Vietnam

- The Psychological First Aid Handbook

Teaching

- Drills Manual - Rory Miller

- Training at the Speed of Life

Resource Links